Dunes

Porcelain is considered the most highly regarded type of ceramic because of its delicacy, strength and brilliant whiteness. But traditionally it has been confined to small objects. Despite numerous efforts to unravel all the mysteries of porcelain, transcending distant times, cultures, and places, one last mystery remained unsolved even by its inventors: how to scale porcelain to large sizes.

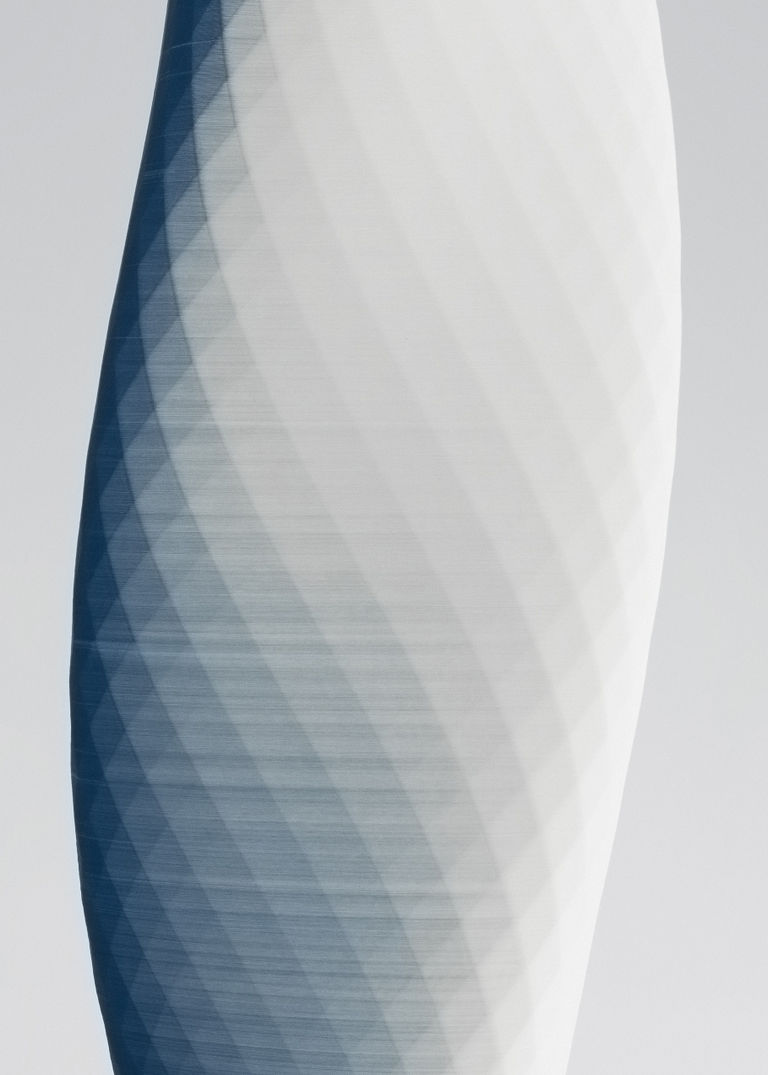

Unlike other clays, porcelain softens in the kiln. Due to the weight porcelain reaches in large scales, larger objects collapse during firing. This inevitably results in cracks and deformations. To avoid collapse, those who did venture into large-scale work had to compromise the purity of the clay, using mixtures that melt less but loosen the properties of whiteness, translucency and finesse of porcelain. Or they restricted themselves to stable, balanced forms that require supports, or, most frequently, to self-supporting round forms.

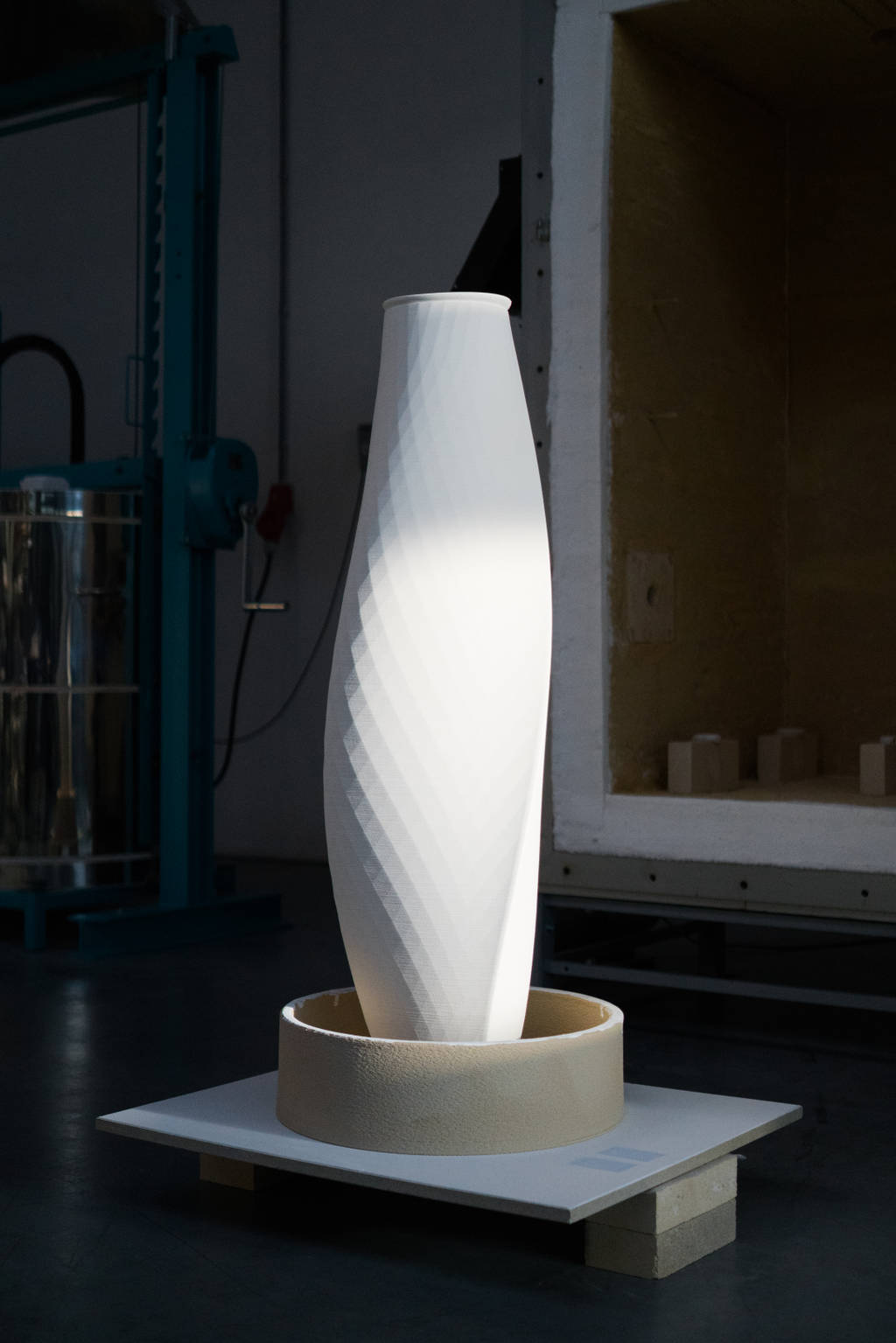

Olivier van Herpt built a new 3D printer capable of forming the thinnest porcelain ever possible on a large scale, making it light enough to avoid collapsing in the kiln despite its size, thereby allowing for large-scale forms without the previous limitations.

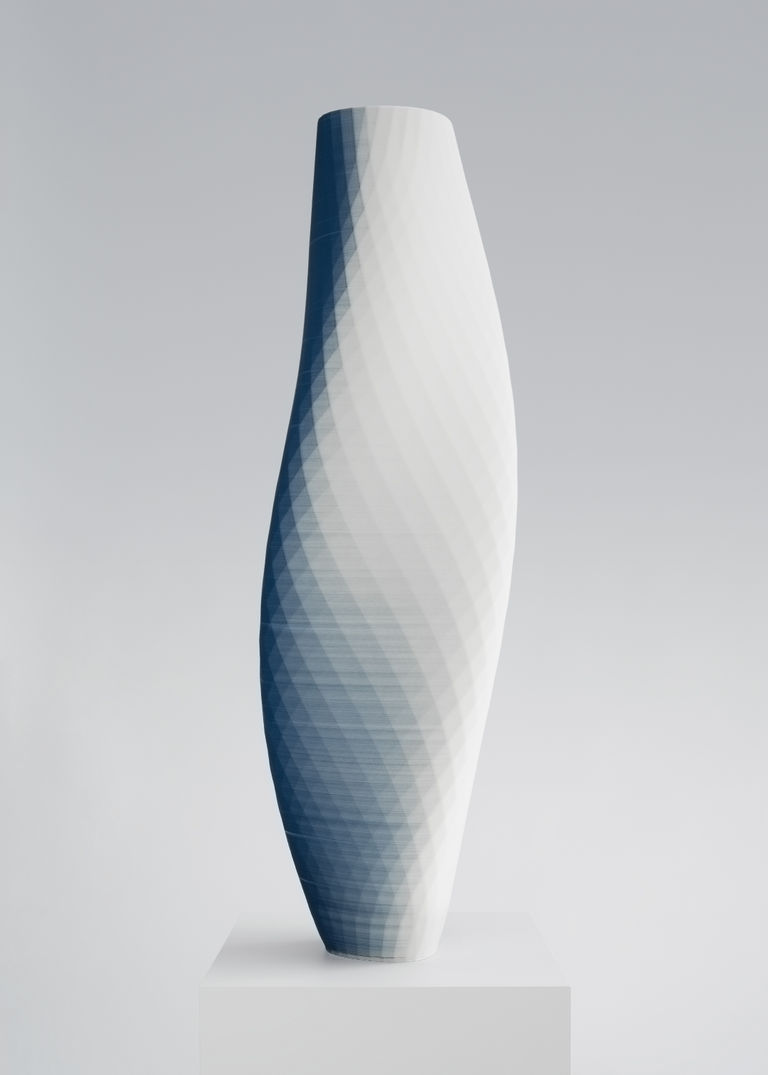

With his new machine he embarked on the painstaking process of unraveling the enduring mystery. Instead of resorting to alternative clay formulations or limiting shapes, he did something considered impossible. He challenged the true white porcelain, also known as hard-paste porcelain, to take on dynamic and asymmetric forms totally unsupported. These measure more than a meter in height. While keeping the form unchanged, he refined his recipe based on insights provided by the form itself.

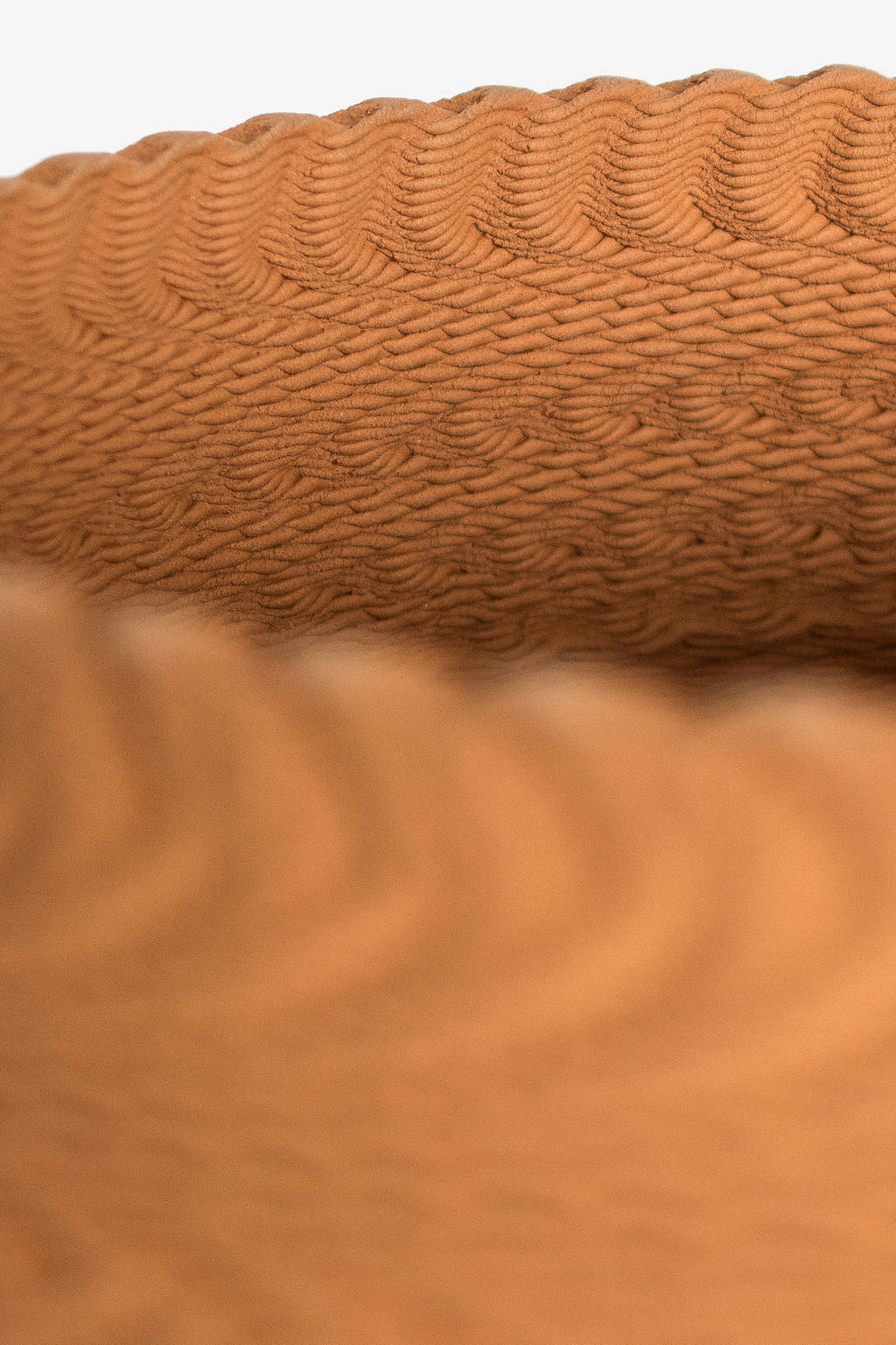

Van Herpt’s recipe involves innovations not only in his printing technique but also in drying and firing, to guarantee a uniform shrinkage. During these stages, a dramatic shrinkage of 30 centimeters happened in his pieces because of the use of the pure white porcelain, which has the highest shrinkage of all clays. Van Herpt faced the challenge by building digitally controlled drying chambers to ensure the large pieces dried evenly. He also 3D-printed the thin fire-clay reusable saggars, the containers that protect objects being fired in a kiln. This spreads the heat and allows for uniform firing.

Each object took Van Herpt weeks to create, with the final result only revealed after opening the kiln. He had to repeat the process 26 times before obtaining the perfect form, undamaged from the firing without cracks or deformations. After three years, Van Herpt perfected his method, revising ancient techniques and developing new tools, achieving not only the form but also its mirrored counterpart. Departing from the tradition of round forms, which when mirrored are identical, non-round forms when mirrored result in different forms. This validated his recipe and unlocked the last secret of porcelain.